The Spirit of Electricity: Genesis of a Masterwork

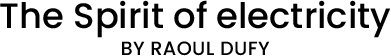

La Fée Électricité (The Spirit of Electricity) was designed and created by Raoul Dufy for the Light and Electricity Pavilion at the International Exhibition of Art and Technology in Modern Life in Paris, in 1937. Running from 4 May to 25 November, the event extended from the Champ de Mars to the Trocadero and from the Eiffel Tower to the Invalides.

In preparation since 1932 and envisaged as a celebration of peace and progress, the exhibition took place in a climate of international tension which would lead to war two years later and, in France, to an economic crisis that had already triggered a wave of strikes in 1936. This context left a number of pavilions unfinished when the exhibition opened, but the event, spread over 105 hectares, was a huge success, involving 300 pavilions, 51 countries and 32 million visitors, together with 348 painters, 257 sculptors and 118 decorators.

As the main contractor for the construction of the Light and Electricity Pavilion, the Compagnie Parisienne de Distribution d’Électricité (CPDE), a consortium of the French capital’s electricity suppliers, entrusted the project to the modernist architect Robert Mallet-Stevens.

Situated at the far end of the Champ de Mars, the finely honed building some 100 meters long and 20 meters high was slightly curved, allowing the projection of light and films on the façade after dark, using Henri Chrétien’s new “Hypergonar” widescreen process.

Paris 1937 – The Light and Electricity Pavilion – Installing the projection box

Set on the roof of the pavilion, the new Ouessant lighthouse lit up the entire exhibition site, with two copper solenoid columns generating an electric arc seven metres long. Facing the installation was a statue by Robert Wlérick of Zeus with his thunderbolt.

High-frequency electric arc. Length 7 metres, power 200Kw, several million volts, constructed by the

CPDE.

In the foreground, the statue of Zeus. In the background, the projection box, aligned with the Eiffel tower.

In the main hall of the pavilion visitors discovered Raoul Dufy’s monumental The Spirit of Electricity. Circuit breakers, turbines and other electrical machines were displayed immediately in front of the work.

Inside the pavilion: The main hall, with Raoul Dufy’s fresco and the 500,000-volt circuit breaker

Inside the pavilion: The main hall, with Raoul Dufy’s fresco and the 500,000-volt circuit breaker

The pavilion was also home to the exhibition The Social Role of Light, designed by Georges-Henri Pingusson and adjacent to The Spirit of Electricity.

The Pavilion of Light and Electricity – Interior – Model home 1937

The Pavilion of Light and Electricity – Interior – The Hermès window

Making the fresco

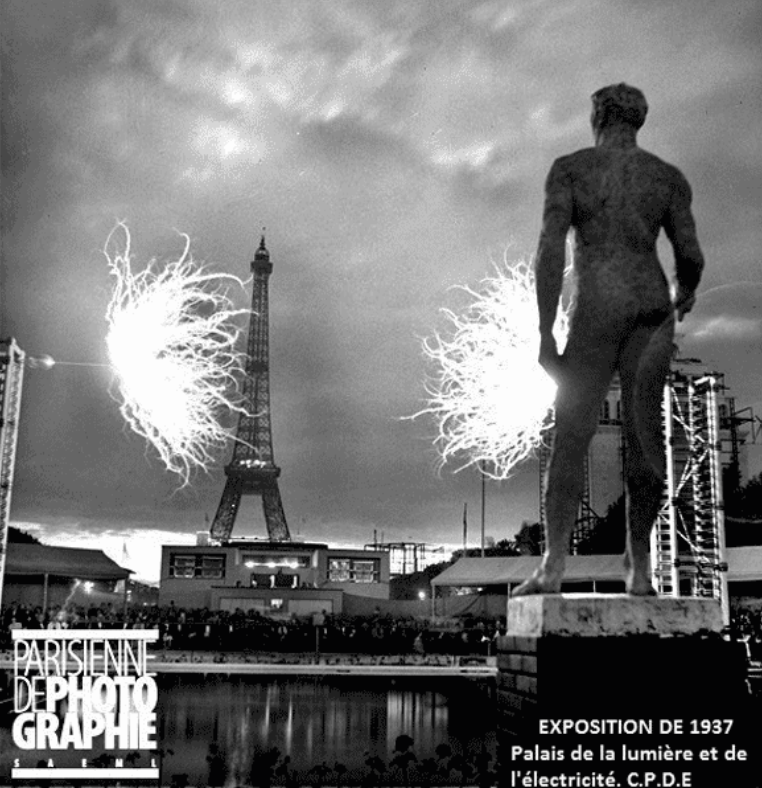

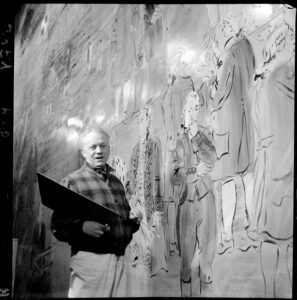

It was not until 7 July 1936 that Raoul Dufy was commissioned to paint the fresco. Aged 61, he was recognised for his capacity to adapt to the entire range of artistic and decorative techniques. He had already created interior decors, notably for Doctor Viard in Paris (1927–1933) and Arthur Weisweiller’s Villa L’Altana in Antibes (1927–1929).

For the Pavilion of Light and Electricity, however, the conditions were not the same: he had to complete this fresco in eleven months, including the time needed for documentation. Dufy took up the gauntlet and proved an outstanding master and commander: nothing slipped by him. The technical documentation was collected by his brother Jean Dufy with the help of Henri Volkringer, a lecturer at the Sorbonne seconded to the CPDE, and author of a remarkable history of physics. Raoul Dufy himself took notes and consulted various experts.

Abandoning canvas as a support, he opted for 250 meticulously carpentered plywood panels, each measuring 2 x 1.2 metres, slightly incurved and coated with heated rabbit skin glue. In the shuttered factory in Saint Ouen which had been made available to him as a workshop, Dufy closely monitored the drying and sanding process. Once painted, the panels were screwed to a metal frame. Dufy worked hand-in-hand with the chemist Jacques Maroger, director of the Louvre’s research laboratory, who developed the Maroger process, inspired by the old masters: “a resinous oil emulsion in gum water”. With it he could paint and repaint without too much delay. The ductility and transparency of the paint made it look like watercolour. Dufy had his pigments ground by the Bourgeois company in Montreuil-sous-Bois, under the supervision of Maroger himself. In all, he used 500 kg of paint.

He made numerous sketches, drawings, 1:10 scale paintings and squared-up tracing paper drawings for transferring the outlines of his motifs onto photosensitive glass plates. Using magic lanterns, these ancestors of the photographic slide were then projected onto the panels to the required scale. Two assistants, André Robert and Monsieur Paulet, with Dufy’s brother Jean, redrew the projected outlines with an ink composed of shellac and bluish smoke black. Everything else was the work of the artist.

A model and a lithograph

Under the terms of the contract between Dufy and the CPDE, the artist also had to produce a maquette of the work, and in May 1937 he wrote to them, “I am ready, perhaps not immediately, to execute the model I owe you. It would perhaps be useful to fix the dimensions according to the location you have in mind for it.” According to a report from the EDF electricity company dated 3 February 1954, the model was delivered in January 1938; it was therefore made after the main project and according to the drawings. It was reworked by the artist between 1951 and 1952, when the lithograph was commissioned.

In 1951 Gabriel Dessus, director of Électricité de France (EDF) and previously chief engineer at the CPDE – it was he who had chosen Dufy for the Pavilion of Light and Electricity – asked the publisher Pierre Bérès to look into the production of an edition of The Spirit of Electricity. Bérès entrusted the project to Fernand Mourlot, a master printer and lithographer much respected in the art world, assisted by his brother Maurice and Charles Sorlier. In May 1951 Mourlot had just returned from the United States, where he had spent a year treating his polyarthritis and undergoing the first clinical tests of cortisone. Initially opposed to applying the process of lithography to the original project, he ultimately took on the task, which he supervised as a true professional, attentive to transition and transfer, and to colour and detail. When a first 1:10-scale lithograph was finally arrived at, Dufy reworked the motifs and colours with gouache and readjusted the proportions. He used the original 1936 sketch as a model for the corrections, while at the same time returning to his drawings to track down the missing details of the sketch. According to art historian Bernard Dorival, he was entirely satisfied with his work, which gave his sketch and the lithograph a more finished, more “human” character than the main project, in which he detected certain weaknesses.

The lithograph was completed in June 1953: 10 plates measuring 100 x 60 cm laid end to end. It was printed in an edition of 350 copies on watermarked Arches paper. At the time it was the largest lithograph ever produced, requiring an enormous amount of work, with two hundred inkings per plate for more than twenty colours.

Dufy died before the lithograph was completed, and only ever saw the two plates of the central section. “My sole regret,” said Fernand Mourlot, “is that he only corrected a few panels and never saw the finished work in its entirety, in May 1953.” More than a reproduction, this is a replica.

Finding a title

The French title, La Fée Électricité – literally “The Electricity Fairy” – was not Dufy’s doing. We do not know what he had in mind: History of Electricity perhaps, or Electricity through the Ages, or To the Glory of Electricity. It was the art historian Bernard Dorival who first came up with La Fée Électricité in 1954, borrowing from French writer Paul Morand’s childhood impression of the lights of the 1900 Universal Exhibition. Invoking the Olympus of the gods, Dufy entrusts two messengers, Hermes and Iris, with the following missions: Hermes is to transmit to mortals the riches obtained thanks to electricity; Iris is to spread light and sound throughout the world. This winged goddess is reminiscent of a magician, a good fairy, and this is undoubtedly what influenced Bernard Dorival’s choice.

Raoul Dufy

Raoul Dufy started out as a painter at the very beginning of the 20th century, alongside the Fauves Henri Matisse and André Derain. Dufy was interested in everything, making no distinction between major and minor art. An excellent wood engraver, he illustrated books by eminent writers of the time, among them Apollinaire’s Bestiaire, recognised as a masterpiece from the moment of its appearance in 1911 onwards. Spotted by the great fashion designer Paul Poiret, he discovered textile design, a field he worked in for over seventeen years for silk manufacturer Bianchini Ferrier, without ever ceasing to paint. In the 1920s he lit on ceramics, which he practised successfully with Artigas. Then interior decoration commissions started coming in – for the state-run Mobilier National furniture collection, the apartment of art collector Dr Viard in Paris, Arthur Weisweiller’s Villa L’Altana in Antibes – which kept him busy from 1927 to 1933, forcing him to give up his textile drawings. He was also called upon to design the swimming pool for the liner Normandie, which unfortunately was never built. He was one of the very first artists selected for the 1937 exhibition.

The move to the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris

In 1937, the contract of the concessionaire, the CPDE, which was nationalised after the war and became Électricité de France (EDF), stipulated that the company had the use of the pavilion while the City of Paris was the bare owner. In 1964, EDF decided to donate The Spirit of Electricity to the future Museum of Modern Art, which opened its doors in 1964. A room in the museum and the curvature of the fresco had to be modified to accommodate it.

The Spirit of Electricity – description of the artwork

Like a symphonic poem, this large-scale decorative work depicts the progress due to the invention and observation of electricity by unfolding not only its frieze of scientists and inventors, but also the repercussions of their discoveries on everyday life. Dufy used collage to create small, photomontage-inspired sketches that fit together and change the scale: there is no perspective, no horizon to improve the connection between the scenes. He gives the large areas of flat colour the function of visually interlinking the objects.

Reading counter-clockwise, the “poetic, historical and pictorial” work starts with the beginning of the world, as Dufy explained in an interview. Next comes Antiquity, symbolised by a sacred wood where a shepherd and his goats relax peacefully, while behind them three great scholars of the period are engaged in discussion. There follows an intermediate period, with progress making a very modest contribution to agricultural work, then the last period, that of industrialisation and the urbanisation of the contemporary world.

At the centre of this panorama, the gods of Olympus form a kind of temple pediment, benevolently presiding over the distribution of wealth made possible by the abandonment of lightning, the symbol of electricity and its application to the mortal world. They send their two messengers, Hermes with his horn of plenty overlooking the electricity plant, forming the link between the gods and the earthly world, and Iris, goddess of the rainbow, messenger of the gods, who comes at night to illuminate the capitals of the world and to set in motion the industrial age and the leisure activities of today’s humanity.

Day is represented to the right by the sun beaming down, while to the left the world is plunged into night, represented by the crescent moon and the stars.

The wellsprings of this masterwork are many and varied: certain painters belonging to Dufy’s personal pantheon were a source of inspiration, among them Claude Lorrain (1600–1682) and Claude Monet (1840–1926). Dufy also drew on his own works for themes that were dear to him. Nor should we forget such artists-decorators-graphic artists of his time as Paul Colin (1892–1985), Cassandre (901–1968) and Jean Carlu (1900–1997), and not least a photographer present during the making of the work: François Kollar (1904–1979), who had just finished his immense project for the publication La France travaille. It is highly probable that Dufy drew on these sources, not to mention the mass of documentation available on science and scientists, such as Les merveilles de la science (1867–1869) by Louis Figuier (1819–1894).